Abstract

As Twitter has become a more popular source for news and communication alike, it has also been seen as a large platform to preach against the mainstream media. With the boom of “citizen journalism” through Twitter, journalists have also had to adapt to include the tweets of citizens in their reports by staying on top of their social media accounts. This study seeks to determine how activists have criticized the media on Twitter and how journalists have used the tweets of citizens to influence their own work by looking into the tweets of influential journalists and activists during the events which took place in Ferguson, Missouri in August, 2014.

Introduction

Over the years, many people have sought out news sources in the media to gain an awareness of current events. With media news sources oftentimes advertising that they are trusted by the masses, they become trusted by the masses, thus demonstrating a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy. As of late, however, more and more people have brought the news sources that are deemed “trustworthy” into question, oftentimes sharing alternative theories of events or even satirical news articles over social media (Lee 2010; Jones 2004). The events which took place in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014 displayed evidence in the change in many individuals from a trust in the media to a criticism of it. The media’s portrayal of the events in Ferguson – as well as its key players – were often displaying characteristics of conflict theory with regard to race: with more White journalists in the media than Black journalists, and with more people reporting the events taking place from outside of Ferguson than in Ferguson, many people found that comments made by the media were reproducing the notion that White people were seen as the “haves” and Black people were viewed as the “have nots” of society (Anderson, 2014). Through communication on Twitter and other forms of social media, many members of the nation were able to facilitate a conversation about the presence of inequality and the lack of trust in popular news sources. Is social media in part to blame for influencing a change in American values? If so, how can we see this change occurring when viewing citizen responses to the news on social media? Furthermore, with the voices of the American public on such a large platform, how have journalists been adapting to the concept of citizen journalism?

Background

Although the events which took place in Ferguson brought about a display of widespread public distrust of the media, it was not the first instance in which people were skeptical of the news as told by corporate media outlets. Studies have been conducted which display an ongoing trend of media skepticism (Lee, 2010; Jones, 2004). The studies done by Lee and Jones both conclude that one’s trust in the media is heavily influenced by politics. According to the research conducted by Lee, individuals were likely to be skeptical of the media due to a distrust in politics as well as their own political ideologies (2010). Jones found similar data to infer that distrust in the government and political ideology were likely to determine the strength of one’s distrust in the media (2004). However, he also noted that Conservatives were the group in the study to most likely claim that they did not trust the media, which was assumed to be due to their infamous, yet contested liberal biases. The idea that a distrust in the media is often linked to a distrust in the government, however, is contradictory to the claim made by Jones that the relationship between the media and politics since Vietnam and Watergate has been described by Jones as “adversarial”: the media and the government do not relay the same messages to the public despite widespread belief that this is the case.

Within the studies of both Lee and Jones revolved around surveying Americans to gain a better understanding of the general public’s views on the media. Both studies referred to data collected through the National Election Studies (NES) of the Center for Political Studies at the University of Michigan (2010; 2004). More particularly, both studies centered their data collection around the question “how much of the time do you think you can trust the media to report the news fairly?” Answers ranged from “just about always” to “none of the time” and were coded using a five-point Likert scale.

Aside from the results of their studies, both Lee and Jones present reasoning derived from past research that are attributed to the distrust in the media with regard to politics. Many people do not trust the media because they oftentimes make attempts to interpret the news rather than just report the news (Jones, 2004). It is also noted that Americans are unsatisfied with the coverage of political news as if it was a game: rather than keeping society informed of political platforms, the media is quick to announce who is winning in the polls and what strategies politicians are using to recruit voters.

With the booming popularity of citizen journalism, however, corporate media journalists have had to adjust to incorporate the inevitably present voices of the American public, oftentimes to cater to the mistrust in corporate news stations (Kim, Kim, Lee, Oh, and Lee, 2015). It has become an expectation for journalists to receive news from social media users which they can then investigate and report to a wider audience. However, it has been found that American journalists oftentimes disregard the tweets of the public when developing news stories and look to the ideas and opinions of more prominent figures on social media. Rather, they associate with those of prestige – such as celebrities and politicians – or those whom are similar to them, which is known as a homophily (Himelboim, Sweetser, Tinkham, Cameron, Danelo, and West, 2014).

Media and Media Distrust

In past research, media has been conceptualized as corporate news stations and newspaper publications (Lee, 2010; Jones, 2004). As for this study, media is conceptualized as not only corporate news stations and newspaper publications, but also the “Indie” news companies – as some journalists in the data set describe them – and the journalists associated with both corporate and Indie news companies. Similar to the conceptualization of previous literature, media distrust is conceptualized as the perception of bias within the media (Lee, 2010).

Methods

The data used in this analysis comes from Pulsar, a platform which specializes in the monitoring of social media. Access was granted to tweets from 45 journalists and 47 activists who actively tweeted using the phrase “#Ferguson” from August 8, 2014 – the night before the shooting of Michael Brown – to December 31, 2014. For this particular study, the data set was narrowed down to the tweets from August 9 through August 14, 2014 which contained the words “journalist,” “journalism,” “media,” “reporter,” or “reporting.” These particular filters were used in order to better find the tweets within the data set which discussed the media. By filtering the sample to a specific time frame and basing it off of the use of key words, the new sample yielded 4.23 percent of the tweets of the old data set, or 308 tweets in total.

This research was conducted by performing content analysis, which the University of Georgia’s Terry College of Business defines as “a research technique used to make replicable and valid inferences by interpreting and coding textual material” (2012). In the case of this research, the textual material consisted of 76 tweets which were coded by tagging the tweets into five separate groups: tweets regarding distrust in the media, tweets defending the media, media meta-discourse, retweets regarding distrust in the media, and retweets displaying trust in the media or defense of the media. Examples of each of these tweets can be found in Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. The messages displaying trust and distrust in the media are divided into groups of tweets and retweets in order to gain a larger understanding of the influence of those in the sample. Because the tweeters in the sample set were some of those with the largest reach during the events which took place in Ferguson, it would be important to observe their communication patterns. Were they tweeting their own ideas or sharing the ideas of others on their large platforms? Did they gain their large followings by “live-tweeting” the events or by retweeting those who may have been on the scene or developed ideas surrounding what was taking place? Furthermore, by sorting the tweets into five different tags, it is easier to see the views of the majority of the sample set with respect to the media.

Along with the content analysis, the tweets in the sample set were taken together to create a network map. A network map is oftentimes used in analysis of social media in order to view the relationships that people have with each other online. Smith et al., for example, utilized network maps in order to define multiple topic networks on Twitter, from “polarized crowds” which consist of people who only associate with those with the same ideological views to “community clusters” which consist of small hubs who are interested in discussing the same topic (2014). The network map was created using the algorithms developed by the Pulsar Platform. With the map, it is evident to see who each person in the sample communicated with as well as who within the sample was mentioned the most. This was beneficial in determining whether those who seem to share similar ideas or were “live-tweeting” from the Ferguson protests had any associations with each other during this time frame. By finding associations with network users within this sample set, it was easier to determine whether there is a homophily among the users in this sample set.

Hypothesis

Through content analysis of tweets in the sample of users on the night of the Michael Brown shooting and the five days which followed, it is expected that the majority of tweets from activists discussing the mainstream media will be those of criticism. Because major issues surrounding the shooting of Michael Brown were his portrayal by the major news sources and the interpretation by the media of the protests which followed, it is assumed that activists would be quick to set the record straight with the media. The majority of tweets from journalists, however, are expected to be those of media meta-discourse. Because they are expected to remain professional despite their arguably biased news stories, the only references journalists are expected to have toward the media are those which are news stories.

In determining how journalists had adjusted to the strong citizen voices during the events in Ferguson, it is hypothesized that journalists will retweet photos taken and videos recorded by activists. They may have also been likely to quote citizen tweeters if they were directly involved in the protests that ensued. Because they do not use Twitter very often for the purposes of communicating with others, it is unlikely that the reuse of citizen posts is common among journalists during this time (Kim et al., 2015).

Results

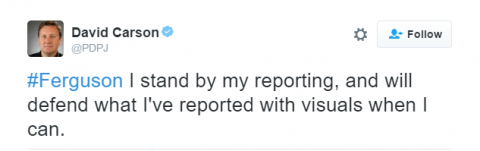

Out of the 308 tweets available in the given time frame, 76 tweets were each able to fit within one of the five tags for analysis. Of these 76 tweets, 22 tweets – about 29 percent – were tagged as media defense. 16 of the 22 tweets were posted by journalists. 20 of the 76 tweets were tagged as media meta-discourse. Of the tweets tagged as media meta-discourse, 13 were tweeted by activists. 15 tweets were sorted under the “media criticism” tag, and 13 of these 15 tweets were posted by activists. There were 11 tweets tagged as media trust retweets as well as 12 tweets tagged as media distrust retweets. Of the 11 retweets expressing trust in the media, 8 were retweeted by journalists. Of the 12 retweets expressing media distrust, 11 were retweeted by activists.

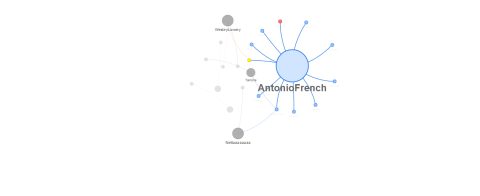

In looking at the network map, it is evident that Antonio French – an activist – had the biggest influence on Twitter within this sample as his circle on the map is the largest and has the most connections. The second largest circles on the map are those of Johnetta Elzie and Wesley Lowery, an activist and a journalist, respectively. However, Elzie only has a reach to two Twitter users in this sample set while Lowery’s reach only extends to three. The other Twitter users within the network map only reach to one or two other users within the map.

Discussion/Conclusion

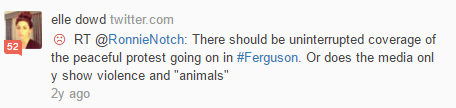

Through the content analysis of tweets from the sample set between August 9, 2014 and August 14, 2014, it was evident that most of the discussion of media was considered to be defending the media rather than criticizing it. Much of this could have been due to the “media blackout” in Ferguson in which almost all media was forced out of town by the Ferguson Police Department and those journalists who planned to enter Ferguson were kept out. The media was tweeting to defend their presumed right to cover the news. However, there were some activists who also were defending the media during the event of the blackout. Elle Dowd, for example, retweeted “Media needs to stand fast in #Ferguson. You have a right to report the news, and we have a right to hear it. #dontleave #standstrong.” Because these tweets were posted during the initial days of protest in Ferguson, activists were likely to want journalists present during the events which took place as the journalists are considered to be the “network gatekeepers,” or those who are able to spread word of events to mass numbers of people at a fast rate (Meraz and Papacharissi, 2013).

While the tweets expressing a defense of the media were oftentimes related to the demand of media presence within Ferguson, the retweets displaying trust in the media – though assumed to be similar – mostly consisted of journalists retweeting praise they received regarding their coverage of the events taking place. Many of these retweets did contain the word “trust” or “trustworthy” in them, which could be inferred as a means of persuading a user’s Twitter audience to believe the news that the journalists deemed “trustworthy” or “unbiased” are reporting.

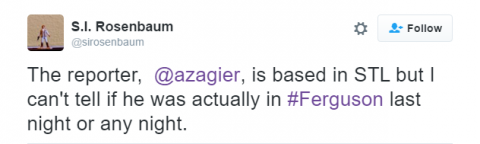

While it was hypothesized that mostly journalists’ tweets would most likely fall under the media meta-discourse category, the majority of tweets under this tag were those of activists. They would oftentimes report the status of the media during the blackout or report any sort of sighting of the media. Many activists posted updates regarding location in order to gather people around the area. Furthermore, activists were sharing instances in which journalists were getting involved in altercations with the police. Many of the activists in the sample sought to share stories of the events whenever they witnessed something happen, and discussing the media would be crucial in achieving that goal as the media played a crucial role in the events which were taking place in Ferguson.

The media criticism and tweets which expressed distrust in the media were similar in nature. Activists were likely to criticize the wording that the media used to portray the events taking place as well as the use of common “Black” stereotypes within news stories. For example, one user retweeted the message “Just want all my non-St. Louis followers to understand that #Ferguson is not in the hood and is not a bad area, despite media reports.” This demonstrates an instance in which a user believed the media to be misrepresenting the setting of the shooting and the protests alike. Other tweets reflect the notion of the media not covering the Ferguson protests enough: one user chastised the press for covering the death of Robin Williams more than the movement happening in his hometown. Those who are considered to be journalists who tweeted criticism of the media noted that they were “indie” journalists, or not part of the mainstream media.

When viewing the network map, it was evident that Antonio French was the most discussed user of the sample set and his tweets had the widest reach among the users within the sample. By viewing the coinciding tweets, it could be concluded that the network map was surrounding Antonio French because he was not only tweeting the news, but also becoming a part of the news: during this time frame, French was arrested and spent time in jail. News spread throughout this sample – and presumably many other Twitter communities – which sparked a growth in mentions of French and was likely to spark a growth in followers as well.

Though small, the network map demonstrates a group of community clusters within this sample (Smith, Rainie, Schneiderman, and Himelboim, 2014). Though French has a wide reach spanning the majority of users within the sample during this time frame, the rest of the users in the sample only associated with one or two other users. Smith et al. define a community cluster as a “few hubs each with its own audience, influencers, and sources of information.” Because of the small amounts of interaction among the users within the sample, it can be inferred that their ideas of media criticism or defense were not stemming off of one another, but rather being shared among different communities. This shows that the ideas that the users shared were likely to have been replicated among different communities.

Limitations to this study included the available size of the sample and the restriction to only tweets using the hashtag “#Ferguson” Or the keyword “Ferguson.” The data set within the Pulsar platform only consisted of 92 Twitter users – 46 activists and 46 journalists – who actively tweeted about Ferguson during the time which the events occurred. These people had the biggest influence on Twitter. Although sampling those with a wider reach is beneficial to understanding the most popular ideas of the protests at the time, it does not account for the tweets of many residents of Ferguson because of the influence that big data has on what we view (Weller, Bruns, Burgess, Mahrt, Puschmann, 2014). Furthermore, many tweets were likely to be posted without the “#Ferguson” hashtag. Therefore, many tweets were unable to be collected regarding the events in Ferguson, especially those which were posted on the night which Michael Brown was shot.

In analyzing the tweets of prominent activists and journalists who actively covered the events in Ferguson via Twitter, it is evident that the goals of the two groups differed. Those who were considered activists were more likely than journalists to tweet messages which criticized the media or report news on the media. Those who were journalists were more likely to tweet messages which defend the media; in particular, they were more likely to defend their right to cover the events which were taking place in Ferguson despite the “media blackout.” The results of this study demonstrate that during the events in Ferguson from the night of the shooting of Michael Brown and the five following days, activists worked to either gain media coverage of the events or criticize the portrayal of the events by the media while journalists used Twitter to gain news stories from those in Ferguson and defend their presumed right to cover such stories.

Works Cited

Anderson, M. (2014). As News Business Takes A Hit, The Number of Black Journalists Declines. Retrieved May 1, 2016 from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/08/01/as-news-business-takes-a...

Himelboim, I., Sweetser, K., Tinkham, S., Cameron, K., Danelo, M., and West, K. (2014). Valence-Based Homophily on Twitter: Network Analysis of Emotions and Political Talk in the 2012 Election. New Media and Society.

Jones, D. A. (2004). Why Americans Don't Trust the Media: A Preliminary Analysis. The International Journal of Press/Politics.

Kim, Y., Kim, Y., Suk Lee, J., Oh, J., & Yeon Lee, N. (2014). Tweeting the Public: Journalists' Twitter Use, Attitudes Toward the Public's Tweets, and the Relationship With the Public. Information, Communication & Society.

Lee, T. (2010). Why They Don't Trust the Media: An Examination of Factors Predicting Trust. American Behavioral Scientist, 54(1), 8-21.

Meraz, S., & Papacharizzi, Z. (2013). Networked Gatekeeping and Networked Framing on #Egypt. The International Journal of Press/Politics.

Smith, M. A., Rainie, L., Shneiderman, B., & Himelboim, I. (2014). Mapping Twitter Topic Networks: From Polarized Crowds to Community Clusters. Retrieved April 24, 2016, from http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/02/20/mapping-twitter-topic-networks-from-polarized-crowds-to-community-clusters/

The University of Georgia Terry College of Business (2012). What Is Content Analysis? Retrieved May 1, 2016 from https://www.terry.uga.edu/management/contentanalysis/research/

Weller, K., Bruns, A., Burgess, J., Mahrt, M., & Puschmann, C. (2014). Twitter and Society. Peter Lang. 45.

- Log in to post comments