Introduction

On August 9, 2014, Michael Brown, police officer Darren Wilson shot and killed an unarmed black teenager, Michael Brown. This day sparked outrage on social media, especially on Twitter. The protests and anger were not solely in reaction to the shooting itself, but also years of institutionalized racism, violence, and oppression by the justice system (Bonilla and Rosa, 2015; Lopez, 2014). The victimization and inferiority of black males would no longer be tolerated; people both on site in Ferguson and online united to raise their voices and end racial inequality. Both activists and journalists were active on Twitter the week immediately following the shooting, providing real time coverage on the protests, police, and breaking news. Activists initiated social movements through Twitter to gain the attention and participation of a global audience (Wells, 2014). While the issue of race was central to the Ferguson protests, this study explored the following questions: in what ways did activists and journalists’ address the issues of race, racism, and police brutality immediately after the shooting? How were these tweets presented in terms of content and form on original tweets? How did journalists and activists’ perspectives on race and racism differ, and who was more objective or affective? How were hashtags used to address racial issues? Through ethnographic content analysis and word cloud and bundle analysis in Pulsar, this study found that both activists and journalists posted about issues related to race and police brutality; each were involved in expressing a voice and raising awareness on racism and police brutality.

Literature Review

Twitter is a social platform where information spreads instantaneously to a global audience, as people unite in one time and place (Bonilla and Rosa, 2015; Tinati, Halforf, Carr, Pope, 2014). Inevitably, social networks form among groups and individuals where people can express themselves and engage in real time public conversation on events, disasters, or elections through following, retweets, @replies, and hashtags (Puschman, Bruns, Majrt, Weller, Burgess, 2014; Rogers, 2014; Tinati et al., 2014). Twitter has become a source for following breaking news and events, while creating a real time story of the action occurring on the scene (Rogers, 2014). By connecting people nationally and globally, Twitter can be used to create social movements (Forminaya, 2014). A major social movement on Twitter emerged from the events in Ferguson in August 2014.

After police officer Darren Wilson shot Michael Brown in Ferguson on August 9, 2014, this news went viral globally on Twitter. The breaking news reached Twitter before the mainstream media (Chaudhry, 2016). The week immediately following the shooting, 3.6 million Twitter posts addressed Michael Brown’s death, and after one month, over eight million tweets used the hashtag Ferguson (Bonilla an Rosa, 2015). As demonstrated on Twitter, the Ferguson events resulted in an uproar against racial inequality, and lead to the establishment of social movements on the media to end institutionalized racism (Jackson, 2016). Through Twitter, activists could reach a global audience and raise awareness about the prevalence of racism in policing. People united online to join the social movement, and activists had the opportunity to express their own voice (Bonilla and Rosa, 2015; Wells, 2014).

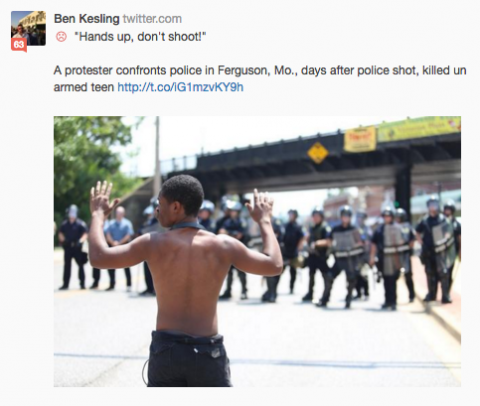

The hashtag was an essential tool in bringing people together globally on social media to fight against racism during the Ferguson events. Through Twitter, participants not on the scene in Ferguson could actively participate in the social movement real time through hashtag campaigns such as “HandsUpDontShoot” and “IfTheyGunnedMeDown” (Bonilla and Rosa, 2015). Activists created hashtag campaigns to raise awareness of and combat police brutality, the vulnerability of black bodies, and racist misrepresentations in the media (Bonilla and Rosa, 2015). Before Michael Brown was killed, he allegedly had his hands up while saying, “don’t shoot”, thus leading to the hashtag HandsUpDontShoot. In using this hashtag, activists often tweeted images of people holding their arms up, demonstrating solidarity and the humanization of black bodies (Bonilla and Rosa, 2015). The hashtag IfTheyGunnedMeDown signified solidarity, and the victimization of black bodies as criminals in the media. Activists used this hashtag with images to portray the criminality and threat of black males solely by their skin color and clothing (Bonilla and Rosa, 2015; Jackson, 2016).

While race was a central issue on Twitter in August 2014, a study by Irfan Chaudhry (2016) observed the discussion and representation of race and racism on Twitter during the first four days after the shooting. The author identified structural racism, race talk, and institutional racism. Chaudhry conceptualized structural racism as a system of inequality, in which whites were at a social advantage. Subcategories of structural racism included “being black”, tweets that illustrated the realities of being black in America, racism, tweets that illustrated an unequal power system where whites were more powerful than blacks (Henry and Tator, 2010 as cited in Chaudhry, 2016), societal bias, tweets that illustrated systematic prejudice towards blacks, and white privilege, tweets that illustrated the privileges of being white (Chaudhry, 2016). Chaudhry conceptualized race talk as tweets that explicitly addressed the theme of race, and institutional racism as racial inequality reinforced by policies, practices, and procedures of institutions. The underrepresentation of blacks in politics and in the police department in Ferguson was an example of institutional racism (Chaudhry, 2016). This study provided a framework for thoroughly categorizing and identifying tweets by journalists and activists in the dataset.

Journalists were influential figures on Twitter during Ferguson. Twitter had transformed traditional journalism, while allowing journalists to report real time credible coverage through text or high quality images, and to interact with their public audiences (Neuberger, Hofe, Nuernbergk, 2014). Professional journalism valued training, technical skills, credibility, accuracy, objectivity, autonomy, legitimacy, and organization, but through social media, journalism had become a conversation (Araiza, Sturm, Istek, Block, 2016; Barnard, 2016; Hedman and Djerf- Pierre, 2013). On social media, there was a less rigid boundary between the private and public, and professional and personal spheres, as journalists engaged and interacted with the public. In doing so, they became more personal and relatable with the common people, and thus gained an accurate perspective from the people themselves (Barnard, 2016; Hedman and Djerf-Pierre, 2013; Kim, Kim, Lee, Oh, Lee, 2014; Meraz and Papacharissi, 2013). In Ferguson, professional journalists tweeted from their personal accounts, and therefore were less distinguishable from and more relatable to non-professional citizen journalists (Araiza et al., 2016).

In contrast to research on the interaction between journalists and the public on social media, according to another study, journalists marginalized and criminalized protestors, a concept known as the “protest paradigm” (Araiza et al., 2016; Meraz and Papacharissi, 2013 ). Journalists portrayed protestors as violent, and ignored public opinion by citing official sources. However, visual journalists expressed sympathy for the protestors (Araiza et al., 2016). Although previous studies have addressed the expression of racial issues on Twitter, and the role of journalists during the Ferguson events, more research was necessary on how journalists and activists tweeted about race and police brutality.

Methods

This study explored the research questions through content analysis, and word cloud and bundle analysis of a dataset that consisted of ninety-two activist-oriented reporters and practicing professional journalists combined. There were 47 activists and 45 journalists in this population who tweeted using the Ferugson hashtag or “Ferguson” keyword. This study collected tweets from August 9, 2014, the day Michael Brown was killed, until November 27, 2014, the day of the Grand Jury announcement that office Darren Wilson would not be charged. To generate original tweets relevant to racial issues and police brutality, I filtered in the key words “Race” OR “Racism” OR “Police” OR “Brutality” into pulsar. This study analyzed tweets from August 9 to August 16, 2014 in order to understand how activists and journalists tweeted about racial issues immediately after the shooting. The final dataset included 1,238 tweets. Of these 1,238, I tagged 257 tweets that were most relevant to the themes of race and police brutality.

I applied ethnographic content analysis, reflexive systematic observation on Twitter, in tagging tweets (Altheide and Schneider, 2013). Through content analysis, I analyzed tweets by comparing and contrasting content based on themes related to racial issues or police brutality (Altheide and Schneider, 2013). Tags grouped tweets into specific categories. Tags included “race”, “police brutality”, “anger towards police”, “hashtag campaigns”, “objective”, and “affective”. These tags identified what and how journalists and activists were tweeting in relation to the themes of systematic or institutional racism, police brutality, objectivity, and affectivity. The tag “race” labeled tweets that directly mentioned “race” or racism” or tweets that addressed the topic indirectly through hashtags such as #justiceformikebrown, #HandsUpDontShoot, #RIPMikeBrown, #DontShoot, #MikeBrown, and #whiteprivilege, or issues related to the policing of black bodies. The tag “police brutality” tagged tweets that addressed the killing of Michael Brown, police violence against protestors, or institutional police brutality. “Anger towards police” tagged tweets that expressed anger against police violence. The “hashtag campaigns” identified tweets that used hashtags relevant to racial issues, and hashtags that were part of social movements to raise awareness of and end racism. Lastly, “objectivity” identified tweets that were factual, and “affectivity” identified tweets that expressed opinion and emotion (Barnard, powerpoint, 2016). This analysis also examined the format of each tweet, as both content, the meaning of a tweet, and format, the visual style of a tweet, each contributed to the meaning, message, and audience interpretation of a tweet (Altheide and Schneider, 2013). Visuals had a powerful effect in portraying race, a topic difficult to communicate through text (Araiza et al., 2016). I generated results by hand counting tags, and comparing and contrasting how journalists and activists used each tag.

I used word cloud analysis to analyze tweets in the dataset to identify the key words journalists and activists used to tweet about issues related to race and police brutality. I used the key words “Race” OR “Racism” OR “Police” OR “Brutality” and filtered in journalists and activists into the dataset separately to compare and contrast each word cloud. The analysis incorporated word bundles to examine the words used with each key word in a tweet, in order to observe patterns in the content of tweets, and how this content differed between activists and journalists.

Results/Discussion

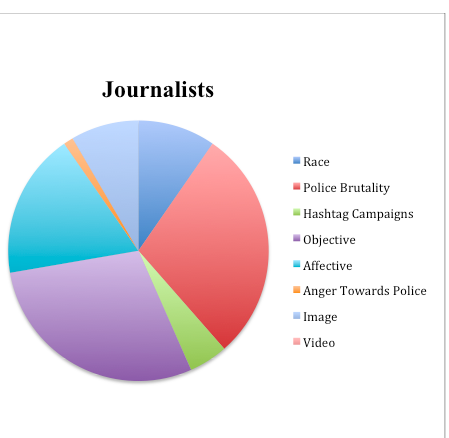

The findings above illustrate the percentages of tags among journalists and activists. Ten percent of journalist posts included content relevant to issues related to race as compared to eleven percent of activist posts, twenty-nine percent of journalist posts included content about police brutality as compared to twenty-four percent of activist posts, five percent of journalist posts included hashtags as compared to twelve percent of activist posts, and one percent of journalist posts expressed anger towards the police as compared to four percent of activist posts. Additionally, twenty-nine percent of journalist posts were objective as compared to nineteen percent of activist posts, and eighteen percent of journalist posts were affective as compared to twenty-three percent of activist posts. Eight percent of journalism posts included visuals as compared to two percent of activist posts. Journalist posts included no video, while five percent of active posts included video.

The higher percentage of objectivity in journalist tweets supported the journalistic values and norms of credibility, legitimacy, and accuracy (Barnard, 2016; Hedman and Djerf-Pierre, 2013). On social media, journalists had to maintain their professional credibility, and distinguish themselves from citizen journalists and the public by reporting newsworthy and objective information (Hedman and Djerf-Pierre, 2013). The higher percentage of affectivity among activist posts confirmed that Twitter allowed activists to express their own voices and opinions during the Ferguson protests. Activists united on Twitter to organize and join social movement to make their voice heard, and used hashtags in forming social movements (Wells, 2014). However, activists like @AntonioFrench also reported real time objective information about protests and police. @AntonioFrench used live video to report on protests, protestors, and police to communicate each scene to the public (Araiza et al., 2016).

Although activists were more likely to post about race, and journalists about police brutality, these percentages were close in number. Therefore, findings were in contrast to the “protest paradigm” as journalists did not criminalize or marginalize protestors (Araiza et al., 2016). Evidence suggested that journalists also expressed discontent towards the police. For example, on August 15, 2014, @elonjames, who worked for This Week in Blackness, posted “violence, brutality, suppression of free speech. Attacks on journalists. Yeah. Let’s believe everything the Police say”. This sarcastic tweet, suggested that the police also victimized journalists, not solely protestors. Therefore, they could relate to the experiences of protestors, and help speak out against police brutality. In being victimized, journalists showed a human face outside of the journalistic world (Barnard, 2016). Many of the journalistic tweets that were relevant to issues about race or police brutality incorporated direct quotes from activists, giving and elevating a public voice to the common people, rather than marginalizing them (Araiza et al., 2016). On August 15, 2014, @GeeDee215 who worked for the National Public Radio tweeted “seeing a lot of ‘well, #Ferguson’s police force is all- white and they have a white mayor because black people don’t vote’ ”! This tweet was both objective and affective because this journalist objectively posted a quote, but the quote by itself was laden with opinion and emotion. Therefore, @GeeDee215 was preserving his credibility as a journalist, but at the same time was voicing the opinion of an activist speaking out against and raising awareness of institutional racism in the justice system and in politics. By quoting activists, activists contributed to and participated in live news coverage. Journalists valued their words as important sources of information (Kim, et al., 2014).

Through the use of professional and high quality images of protests or police militarization, journalists in these findings justified their credibility, but also accurately publicized and represented the experiences of the protestors (Araiza et al., 2016). For example, Wall Street Journal reporter @bkesling tweeted this image below on August 11, 2014.This high quality image depicted an innocent young black male with his arms up in the air. He was facing a line of white militarized police officers. This image portrayed the innocence, victimization, and vulnerability of a black body, a powerful message on systematic racism that could not be communicated solely through text. This journalist was not marginalizing or criminalizing the protestors, but rather visually shedding light on reality.

With exception to @bkesling, the two journalists who expressed anger towards the police, or helped to elevate the voices and experiences of the common people worked for independent news organizations such as This Week in Blackness, or the Intercept, journalism that focused on human rights and equality. However, a journalist who worked for the Washington Post, a mainstream news organization, portrayed the police, and racial issues through a different lens. @WesleyLowery posted “ ‘I've been trying to increase the diversity of the dept since I got here,’ -#Ferguson police chief, says he promoted 2 black superintendents”. Instead of quoting the public, this journalist quoted a police chief, an official source of information (Araiza et al., 2016). This tweet made the police look innocent; the chief defended himself by reporting his efforts to hire a more diverse staff. The chief did not acknowledge the institutional racism that had lead to the underrepresentation of blacks in the Ferguson police department, and the fact that there were only three black police officers out of fifty-three (Lopez, 2016). By reporting from the perspective of the police chief, @WesleyLowery did not report the story from the viewpoint of the people who had been personally victimized by the police. He also tweeted “Ferguson police says ‘I was uncomfortable with that as well w/fact that # MicheaelBrown’s body laid, uncovered in the street after the shooting’ ”. From this perspective, the police were sympathetic for what was done to Michael Brown’s body, and tried to make themselves seem innocent, as though the entire institution was not at fault. The police failed to recognize the systematic victimization of black bodies in the justice system. In tweeting from this perspective, this journalist portrayed a different view to the events in Ferguson, and relied on the police as a credible source.

As opposed to journalists, activists more frequently addressed racism directly and expressed their own reaction to racism and police brutality. For example on August 13, 2014, @SeanSJordan tweeted “seeing police respond to #Ferguson like an occupying army is an ugly eye-opener into how Black Americans must feel every day. How terrifying”. Although affective, this tweet provided insight into the experiences of “being black” in America. Black bodies were vulnerable to policing because the police saw them as threats (Bonilla and Rosa, 2015; Chaudhry, 2016). Black males should not have had to walk outside and fear the police (Lopez, 2016). On August 11, 2014, @Nettaaaaaaaa tweeted “do not blame the people of this city for reacting to years of injustice and racism, BLATANT racism like this. #STL #Ferguson”. This activist fought for the people of Ferguson, and brought attention to the racism that continued to exist. On Twitter, she had the freedom to express her own voice. @Nettaaaaaaaa also tweeted on August 11, 2014, “Kids have to go to school in the morning! can’t why? The POLICE are outside causing CIVIL UNREST, MADNESS, and Mayhem. #Ferguson #STL”. This activist expressed anger, and the harsh reality of what it was like do live in Ferguson after the shooting of Michael Brown. As a result of the police violence, children were not able to attend school. Capital letters in this tweet emphasized the severity of police brutality. Another activist engaged in hashtag campaigns in organizing a protest; @MsPackyetti tweeted on August 14, 2014, “The thing to remember #Ferguson: we STILL need #JusticeforMikeBrown and for the police to be clear: #DONTSHOOT. Don’t forget about TOMORROW”. This tweet illustrated how activists united to form social movements to end and bring awareness to systematic and institutional racism. The use of hashtag campaigns brought activists together to fight for justice and equality.

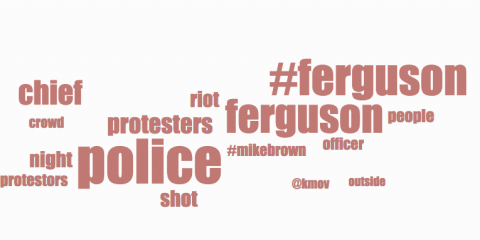

In addition to ethnographic content analysis, word cloud and word bundle analysis also provided interesting and valuable insight into how journalists and activists tweeted about race and police brutality. According to the word cloud on journalists, key words included “protesters”, “police”, “shot”, “chief”, “riot”, and “officer”. In the activist word cloud, key words included “#MikeBrown”, “police”, #stl, “peaceful”, “dept”, “station”, and “gas”. Based on these results, activists were most likely to tweet with hashtag campaigns, and journalists were most likely to tweet about the protestors and riots. However, both journalists and activists tweeted using mutual key words, providing evidence that both reported on similar themes. Based on the word bundle, activists tweeted “peaceful” alongside the words “protest” and “police”, suggesting that activists peacefully protested, and police initiated the violence. Activists tweeted “gas” with “police” and “tear”, illustrating police brutality. Activists used the hashtag MikeBrown with “#stl”, “peaceful”, “people”, “right”, and “police”, and journalists tweeted this hashtag with “shooting”, “officer”, and “chief”. From this finding, journalists used this hashtag to address the shooting of Michael Brown, while activists used this hashtag more so as a hashtag campaign to unite people in solidarity.

Conclusion

From these findings, journalists were more objective and activists were more affective during the week immediately following the shooting of Michael Brown. Journalists preserved their credibility, and activists raised their voices on social media to bring attention to the prevalence of racism in Ferguson. Journalists, like activists expressed anger towards the police, as each were victim to police brutality. In contrast to the “protest paradigm”, journalists primarily working for independent news organizations objectively tweeted about race and police brutality from the perspective of the people (Araiza et al., 2016). In comparison, a journalist who worked for a mainstreams news organization tweeted from the perspective of the police. These findings illustrated the different viewpoints portrayed in the media, and the less rigid boundary between activists and journalists. By quoting activists, journalists provided an authentic and accurate perspective of the protests (Meraz and Papacharissi, 2013). Although an official source, the information provided by the police sugarcoated the realities of racism and police brutality.

Due to the small sample size, and overrepresentation of influential journalists and activists, these findings could not be generalized to the entire population of journalists and activists. The sample was limited to 257 tweets. The analysis was subjective, as I conceptualized each term, and tagged and analyzed each tweet based on my own interpretations. I hand counted the results, and therefore the quantitative data on tags was not exact. Additionally, I was not able to fully analyze why journalists quoted activists and the police. Journalists could have been supporting the activists, and protesting with them, or simply doing their job as a reporter.

Future research could examine the networks between journalists and activists to more closely observe how they interacted on issues related to race and police brutality. Reach and visibility could also be examined to determine whether journalists and activists had more influence in raising awareness on racism and police brutality. It would be interesting to observe the visibility and reach of a journalist post that quoted an official source in comparison to a post that quoted the public, to see which viewpoint the audience supported. Future research could compare and contrast how different states, specifically in the North and the South, reacted to racism and police brutality during Ferguson. Ferguson was a product of systematic and institutional racism, and therefore it was and remains essential to examine the influence of social media in bringing attention to police brutality and racism.

References

Altheide, D. L., & Schneider, C. J. (2013). Ch. 3: Process of qualitative document analysis. Qualitative media analysis (pp. 39-73) Sage.

Araiza Andrés, J., Sturm Aruth, H., , I., Pinar, & Bock Angela, M. (2016). Hands up, Don’t shoot, whose side are you on? journalists tweeting the Ferguson protests. Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies,1-8. doi:10.1177/1532708616634834

Barnard R, S. (2016). 'Tweet or be sacked': Twitter and the new elements of journalistic practice. Journalism, 17(2), 190-207.

Barnard, S. (2016). Lecture Notes W9, day 2 (Powerpoint slides).

Bomilla, Y., & Rosa, J. (2015). #Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politcs of social media in the United States. Æ American Ethnologist: Journal of the Ethnological Society, 42(1), 4-17. doi:10.1111/amet.12112

Chaudhry, I. (2016). “Not so black and white”: Discussions of race on twitter in the aftermath of #Ferguson and the shooting death of mike brown. Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies, 1-9. doi:10.1177/1532708616634814

Fominaya, Cristina Flesher. 2014. “Chapter 6: Social Movements, Media, and Information and Communication Technologies” in Social Movements and Globalization: How Protests, Occupations and Uprisings Are Changing the World. Palgrave Macmillan

Hedman, Ulrika and Monika Djerf-Pierre. 2013. “The Social Journalist.” Digital Journalism 1(3): 368–85.

Jackson, R. (2016). If they gunned me down and criming while white: An examination of twitter campaigns through the lens of citizens’ media. Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies,1-7. doi:10.1177/1532708616634836

Kim, Y., Kim, Y., Lee Suk, J., , O., Jeyoung, & & Lee, N. Y. (2014). Tweeting the public: Journalists' twitter use, attitudes toward the public's tweets, and the relationship with the public. Information, Communication, & Society, 18(4), 443-458. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2014.967267

Lopez, German. 2015. “12 Things You Should Know about the Michael Brown Shooting.” Vox. January 9. http://www.vox.com/cards/mike-brown-protests-ferguson-missouri.

Meraz, Sharon, & Papacharissi, Z. (2013). Networked gatekeeping and networking framin on #Egypt. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 18(2), 138-166. doi:10.1177/1940161212474472

Neuberger, C., Hofe Jo Vom, H., & Nuernbergk, C. (2014). The use of twitter by professional journalists: Restuls of a newsroom survey in Germany. In K. Weller, A. Bruns, J. Burgess, M. Mahrt & C. Puschmann (Eds.), Twitter and society (pp. 345-357). NY: Peter Lang.

Puschmann, C., Bruns, A., Mahrt, M., Weller, K., & Burgess, J. (2014). Epilogue: Why study twitter. In K. Weller, A. Bruns, J. Burgess, M. Mahrt & C. Puschmann (Eds.), Twitter and society (pp. 425-432) Peter Lang.

Rogers, R. (2014). Debanalising twitter: The transformation of an object of study. In K. Weller, A. Bruns, J. Burgess, M. Mahrt & C. Puschmann (Eds.), Twitter and society (pp. x-xxvi) Peter Lang.

Tinati, Ramine, Susan Halford, Leslie Carr, and Catherine Pope. “Big Data: Methodological Challenges and Approaches for Sociological Analysis.” Sociology, February 18, 2014 doi:10.1177/0038038513511561. http://soc.sagepub.com/content/48/4/663

Wells, Georgia. “Ferguson to New York, Social Media Is the Organizer’s Biggest Megaphone.” WSJ Blogs - Digits, December 4, 2014. http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2014/12/04/ferguson-to-new-york-social-media-is-the-organizers-biggest-megaphone/

- Log in to post comments